Saint-Estèphe, which was named ‘Saint-Esteve de Calones’ up until the 18th century (de Calonès meaning small receptacles for carrying wood) was born from the river with the first inhabitants using it as a means of developing commercial partnerships. The numerous streams, brooks and marshes conceal remnants of the region’s past and give us a valuable insight into the history of this beautiful winemaking village.

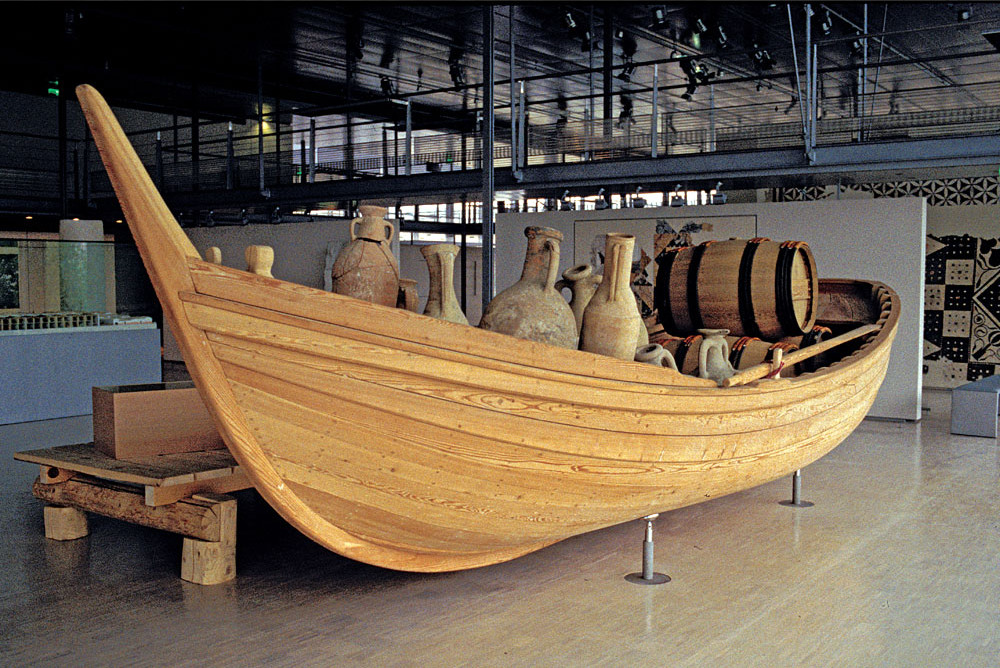

The origins of Saint-Estèphe date back to ancient times. Numerous traces and archaeological ruins attest to a presence on its soil as far back as the Bronze Age (3500 B.C.). Its close proximity to the river made it easy for boatsmen of all origins to purchase local produce and exchange merchandise.

The Gauls of the Médoc, a native Celtic people known as the Médulli, who gave their own name to the Médoc (meaning ‘the land in the middle’ or ‘the middle of the waters’) most likely began to cultivate vines here after being introduced to wines imported from Italy by the Romans.

Although we cannot really speak of viticulture in the Médoc before the Middle Ages, it is highly likely that commercial and cultural relationships between these two peoples contributed to their knowledge of vine growing.

The mystery of Noviamagus! The lost Roman city of Noviamagus, mentioned in ‘Ptolemy’s Geography’, was just as large as the city of Burdigala (now Bordeaux) and was located, according to historians and geographical researchers, near the archaeological site of Brion, close the what is now Saint-Estèphe

Winegrowing in Saint-Estèphe probably dates back to the 13th century. It was initially developed by monks and continued to evolve throughout the Middle Ages. Wine was divine and much more readily consumed than the somewhat doubtful water. Saint-Estèphe is also situated on the Saint-Jacques de Compostelle pilgrimage route (the famous Way of Saint James). Arriving from the North for the worship of relics, they braved the dangers and crossed the river before mooring in the port of Saint-Estèphe. They took refuge in the churches of Notre-Dame- Entre-Deux- Arcs (situated at the entrance to the port before being destroyed in 1704) and Notre-Dame- de-Couleys (where Château Meyney now lies). The passage of the pilgrims here attracted numerous tradesmen. ‘La Foire de la Chapelle’ (Chapel Fair) is still held in early September every year and bears witness to this era.

Despite certain periods of unrest, the English Occupation undeniably led to a sustainable economic rise in viticulture. The port of Saint-Estèphe enjoyed close links with the vines and continued to do so up until the 18th century.

The marshy landscapes, formed of small islands, changed drastically as of the 17th century following the drying up of the marshes by the Dutch at the request of Henry IV.

Extrait de la carte du cours de la Garonne, 1759

The marshy landscapes were gradually

replaced by a landscape of vineyards on sunny outcrops until viticulture

became almost the only form of cultivation in the village.

The modern

division of the land into individual plots marked the beginnings of the

wine domaines as we know them today. Wealthy Bordeaux parliamentarians

began to take an interest in this geographical area to the north of

Bordeaux and instigated a veritable colonisation here.

Its rise in popularity was accentuated by the notion of ‘Cru’ which was developed in the early 18th century. The wines, referred to as ‘the New French Claret’, improved considerably in quality and earned themselves a reputation with international consumers.

Although the largest wine domaines belonged to nobility, aristocrats and wealthy wine merchants, Saint-Estèphe still counted a large number of local winemaking families who owned smaller sized domaines.

The original priory barns of the Middle Ages (the ‘Bourdieux’) have long since disappeared and been replaced by châteaux of varying architectural forms. The addition of the attractive word ‘château’ to that of the ‘cru’ was undoubtedly the reason behind the frantic construction of numerous châteaux throughout the 19th century. In the second part of the 19th century, new buyers including wealthy businessmen, merchants and French and foreign bankers began to purchase and develop the estates.

The winemaking village of Saint-Estèphe has remained intrinsically linked to its vineyards, although its deep historical roots have not prevented it from staying at the forefront of innovation and counting some of the world’s most prestigious châteaux to its name. The image of Saint-Estèphe is one of a perfect symbiosis between tradition and modernity.

The appellation counts:

5 Crus Classés (Classified Growths from the 1855 classification)

Around twenty Cru Bourgeois

Around thirty ‘Hors Classés’ (‘Unclassified’)

1 Cru Artisan

1 cooperative cellar

Comments