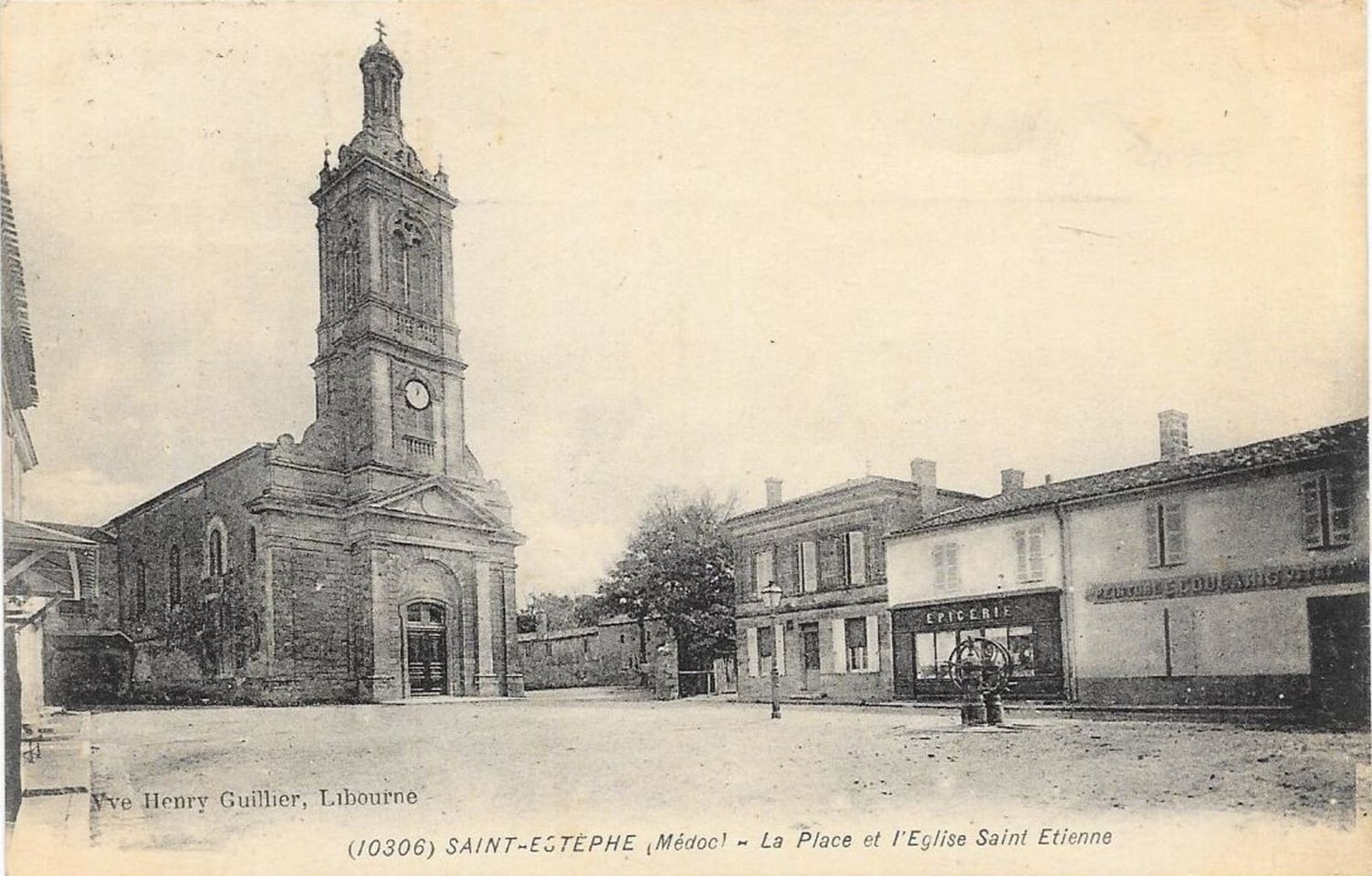

Saint-Estèphe is said to be the transformation in local dialect of “Saint-Etienne” as we are reminded by the church of the same name built in 1764 on the ruins of a Romanesque church. It is known that in early Christianity, churches dedicated to Saint-Etienne were built on the sites of old Roman villas. Saint-Estèphe, which until the 18th Century was called Saint-Esteve de Calones (from “Calonès” meaning small wood-carrying vessels), owes its birth to the River. This river, commonly called ”la rivière”, created a connection between man and land that appears to be stronger here than in other wine regions. It is also known that at the site of the present day port there once stood another church, destroyed in 1704, known as “Notre-Dame-Entre-Deux-Arcs” as it was located on an outcrop of land between two esteys (small streams) forming two arcs. This description conjures up an image of an unusual, almost bizarre, landscape. At the time the peninsula was made up of a series of many islands, a sort of world’s end whose watery milieu would have forced inhabitants to adapt and taught them how to master the environment. It was not until more recent times when the marshes were drained that we could admire the landscape as it is today, mellowed by time and finally revealing its secret. Walking along the bank of the estuary, we can contemplate the many gravelly slopes seeming to greet the river that created them. Yet, way back in time, thousands of years ago, this tranquil looking river was a terrifying sea that tore rocks and pebbles from the distant mountains and carried them off, dropping them here and there, and in so doing gave the soil its bedrock, the essence of the Saint-Estèphe terroir. A terroir

blessed by nature…

I- before the vine, the taming of a secret, unique and changing land, early MASTERY of the environment

From the Bronze Age to the vine

It is in this landscape created by the turbulence of the estuary that Saint-Estèphe has its genesis. Here, the pervading spirit of rural tradition is said to be the result of the land having been occupied from early times. Long before the vine, which appears to date from Gallo-Roman times, and since the middle of the Bronze Age (-3500 BC), Saint-Estèphe has seen a fair amount of human occupation. The area’s metallurgical production was recognized as being one of the most important on the European Atlantic coast. Archaeological relics such as polished axes dating from the Neolithic Period are evidence of local bronze production. Other artifacts such as Gallic coins dating from the Iron Age (800 to 50 BC) indicate that there was a large deposit of iron ore, particularly at a spot known as “l’Hereteyre” meaning “land of iron” in the old Gascon language. Saint-Estèphe’s location on the river edge facilitated the trade and export of its production. The first Bronze and Iron Age inhabitants, living near the water for practical reasons but also careful to occupy the fertile lands and protective hillocks rising above the marshes, gradually developed livestock farming and agriculture. Yet to be known as Saint-Estèphe, this inhabited area also developed because of its location on the river edge that provided a number of shelters that were considered “safe”.

At Saint-Estèphe, men maintain a sacred bond with their land

The river to which Saint-Estèphe owes so much has not only brought prosperity. It should not be forgotten that it opened the door to the numerous invasions and destructions to which the village was victim over many centuries. Its river port location was an open invitation that attracted barbarians and other invaders who sought entry into this secret land. Many legends about the estuary are part of its history.

II- Saint-Estèphe, a land of exchange even in gallo-Roman times,

The Gauls of the Medoc, known as the Medulli – an indigenous Celtic tribe who are said to have given their name to the Medoc - “terre du Milieu” (middle-earth), “milieu des eaux” (middle of the water) - without doubt started to cultivate the vine after becoming familiar with wine imported from Italy by the Romans. Before the Middle Ages we cannot really speak of a wine growing culture in the Medoc, but it is believed that trade and cultural exchanges between these two peoples played a part in the introduction of improvements and innovations in viticulture. The Romans appreciated the skills of the Gauls, particularly in metallurgy, wool weaving and especially wood working techniques, such as cooperage (barrel-making), a judicious invention that our fine wines could not have done without. The Gauls and particularly the Bituriges Vivisques, the founders of Burdigala (Bordeaux), acclimatized the Biturica grape variety, possible ancestor to our Cabernet. The many roman artifacts discovered more or less throughout the appellation area (Aillan, Cos, Meney, l’Hôpital de Mignot, Montrose or in the St Estèphe village), include vases, tiles, coins and axes.

Could Saint-Estèphe’s port be an extension of Noviamagus, the great Gallo-Roman metropolis?

As the reader would have gathered, the river has played a vital role in the history of Saint-Estèphe by permitting ships from all parts of the world to take in supplies of local produce or to trade goods. The many streams, esteys and marshes also played their part in the commune’s history.

Boat moorings discovered at the foot of an old tower in Saint-Corbian, more precisely in a plot of vines belonging to Château Tour des Termes (which means “Lands End”), confirm that there was a large navigation network in the marshes and broad, now dry channels. Marshes that were used until the 18th Century and that once formed a large bay connecting to the Gironde, can still be found near the tower. The present day Château Calon-Ségur is situated on the site of a Gallic oppidum. The boats came to dock as far as “Calon” whose Gallic etymological origin relates to water and stone. From Gallo-Roman times, meeting places were set up at border intersections accessible by water in order to facilitate trade. The marais de Reysson (Reysson marsh) was one such example. It included several harbours, those of Saint-Estèphe, Cadourne, Saint-Germain d’Esteuil and Vertheuil. Invented by the Gauls, and adopted by the Romans, this type of border-market situated along the river edge, of which there were around ten or so in Europe, were often referred to as “new market” or Noviamagus.

It is known that at this time there was another port town as important as that of Burdigala: Noviamagus. There have been numerous theories attempting to pinpoint the location of this town that was probably swallowed up by the waters. Some scholars believe that Saint-Estèphe may have been an extension of Noviamagus or at least included within the same geographical area. Its port may not have died out but might simply have sunk. The discovery of the Brion archaeological site near Saint-Estèphe showed that there were once important buildings in this area. The Romans could have created a new town with significant trading and administrative activity that included a theatre and lavish villas. The Brion site is indicative of a richness of occupancy typically found in large urban centres. This theory is borne out by the ruins of a semi circular theatre of around 2000 seats as large as the Palais Gallien in Bordeaux. The southern part of the Marais de Reysson, located in Saint-Estèphe, is rich in Gallo-Roman finds. Other remains such as those of the Bois-Carré villa, near Saint-Estèphe, located at the edge of the marsh in the Saint-Yzans commune, are important evidence of what was once a great agricultural estate. The numerous objects found, such as tableware of Italian origin, Belgian necklaces and various coins, point to the central role that trading and outside exchanges would have had. It is likely that this busy area was indeed Noviamagus but this town still lies concealed and will continue to nourish legends unless it one day re-emerges from the river on a strong tide.

III- Saint-Estèphe in the middle ages, the first fruits of great wine growing

In the Middle Ages, Saint-Estèphe, along with the rest of the Medoc, went through a difficult period, becoming the theatre for the Guyenne wars. The river, bringer of prosperity and trade in Gallo-Roman times, now served more often to assist barbarian invasions. The early Middle Ages were particularly brutal with the arrival of the Saxons and Visigoths who, it would appear, landed at Saint-Estèphe, pillaging and burning everything in their path. Later came the Muslim invasions and the Vikings in the 9th Century who terrorized the people of the riverbanks. Although the entire Medoc was weakened and became a wild, deserted land for many years, as was to be described later by the 16th Century poet, Etienne de la Boètie, the inhabitants of the shores such as those at Saint-Estèphe, seem to have resisted and contributed to the creation of a new society focused on wine-growing. This viticulture, which seems to have started earlier in Saint-Estèphe than in the other communes, dates back to the 13th Century at least.

Saint-Esteve de Calones, land of pilgrims, the Way of Saint James

Saint-Estèphe was not only a port and relay post frequented by merchant vessels; it was also a port of call for pilgrims on the “route de Saint-Jacques de Compostelle” (The Way of Saint James taking pilgrims to Santiago de Compostela in Spain).

The ‘L’Hôpital de Mignot’ (Mignot Hospital) was founded in the 13th Century by the Commanderie Hospitalière de Saint Jean de Jérusalem (St John of Jerusalem monastery hospital). The hospital subsequently became the Anteilhan Chapel that disappeared in the 19th Century. Many pilgrims and travellers came and took refuge there. Today only the name of the Saint-Estèphe hamlet “ L’Hôpital” is testimony to this past. This is located south-west of the commune at the junction with Cissac where it becomes Cendrayre, just before Coutelin.

Pilgrims from the north, driven by their worship of relics and willing to brave the dangers, were able to dock at various harbours found at the edge of a canal, estey or rouille (ditch) and seek help and hospitality.

At that time there were two other churches within the commune area, in addition to the town’s Romanesque church: Notre-Dame-Entre-Deux-Arcs and Notre-Dame-de-Couleys. Close to the river, it would seem that they were both important places of prayer. Notre-Dame-Entre-Deux-Arcs stood in the present day Saint-Estèphe port. This church was very well attended after the English left Guyenne. In fact the King of France, in order to secure the estuary, banned English merchant ships from sailing up the estuary beyond Notre-Dame-Entre-Deux-Arcs, so these therefore stopped at Saint-Estèphe to get as close as possible to Bordeaux. The Notre-Dame-Entre-Deux-Arcs church was destroyed in 1704 and its stones were used in the construction of the present day village church. Today a small private chapel remains in the port. This port chapel gave its name to the famous Saint-Estèphe “Foire de la Chapelle” (Chapel Fair) that still takes place annually in the port in early September. The origin of this fair, which attracted many stall holders, was the passing through of pilgrims every year on their way to Santiago de Compostela.

The English occupation: a boon for the wine trade

By her marriage in 1152 to Henry II Plantagenet, the future king of England, Eleanor of Aquitaine ensured an enduring sales outlet for Bordeaux wine. We like to picture the beautiful queen visiting Soulac, at the port of the Anglots, taking the Levade (old roman road later called the chemin de la “Reyne” (Queen) to travel through her Medoc lands. During the Hundred Years War, Saint-Estèphe, along with the rest of the Gironde region, was the stage for the English and French to settle old scores. Some remains of towers and fortresses are testaments to this period. Often built on the sites of old Roman camps, these buildings were used for defence as well as to give warning of approaching danger. Château du Breuil in Cissac was one such example. Of Gallo-roman origin, it was a stake in the Franco-English war as it controlled access to the Lafite and Brueil marshes. Despite these conflicts, the river continued to play its part in the trading and transport of goods. The inhabitants understood the importance of trade with England and appeared not to want to take sides in the conflict. It was during this period of Franco-English conflict, which dragged on for over 5 centuries, that Saint-Estèphe really established its vocation as a wine-producing village, also focusing on trade and export. Its Notre Dame Entre Deux Arcs port was extremely busy in the 15th Century. The English had certainly fostered lasting economic growth.

From the 13th Century, the vine gains recognition in Saint-Esteve de Calon, the first wine growers

The spread of Christianity, with the building of monasteries and abbeys, developed the wine growing culture. Wine, symbolizing the blood of Christ, probably brought a new facet to medieval society. Besides the symbolic aspect of communion, wine played an important part in the life of monasteries and priories; it was subject to conventions such as “Better to take a little wine out of necessity than much water out of greed.” Wine was appreciated for several reasons; it comforted travellers and pilgrims, helped nurse the sick and could provide substantial income. In addition, wine making was a sign of prestige and authority.

The example of the Notre Dame de Coleys Priory in Saint-Estèphe is interesting. This has now completely disappeared but it once stood on the site of the present day Château Meyney. Originally the “Maison de Coley” depended on the vast seigneury (landed estate) of Calon. In this area, wine growing goes back a long way and was probably established in Gallo-Roman times. It is known that the Priory existed in 1276 and that, a century before “ planting fever” set in, vines flourished there thanks to the Order of the Feuillants. This was in fact a priory-barn based on a model devised by Cistercian Abbey monks. That meant that farming took place over a vast estate that included polyculture and livestock as well as houses, gardens, huts, farmland, vines, woods, meadows and pastures. It was a real community, an administrative centre with a small port located near the Rouille des Moines, which enabled the transport of passengers and goods. The priory was destroyed then rebuilt in 1662. The Notre Dame de Coleys monks made an important contribution to the development of the Saint-Estèphe vineyards.

By becoming the annex parish to the Archbishopry of Lesparre in the13th Century, controlled by Guy Martin, Lord of Calon, Saint-Esteve de Calone enjoyed a certain prosperity principally from its land planted with “good vines”. These were already very profitable and more so than the cereal that often remained the main crop elsewhere.

The commune was run by the Lord of Calon, owner of the Calon fiefdom, the oldest in Saint-Estèphe. Other fiefdoms would appear to have been important, that of Blanquet, or the vassal seigneury of Lassale de Pez, the Provost’s fiefdom. Pez is also an old wine growing area. Its creation dates from the 15th Century but it mainly owes its vineyards’ early fame to the Pontacs, who also build up Haut-Brion. Pez remained this family’s property until the Revolution, through the Marquis d'Aulède and the Count de Fumel, commander of the province of Guyenne.

The lord was a military leader, tax collector and upholder of the law. He owned his estate with house, mill, wood, gardens and land farmed by tenants who paid him dues. The seigneuries were therefore self-sufficient. Even if the vine was initially grown for the pleasure of the table and to pay dues, it quickly became a source of profit.

The famous 14th Century Canteloup family owned Château de Canteloup on the site where the present day Town Hall now stands. This property, now gone, belonged to Bertrand de Goth, Archbishop of Bordeaux, better known by the name of Pope Clement V. He donated it to his nephew, Arnaud de Canteloup, and the estate remained the property of the Archdiocese of Bordeaux until the Revolution.

Another case: the present day Château Pomys, whose main building has now been converted into a hotel-restaurant, is an example of some of the most beautiful architecture in Saint-Estèphe. Known as the “noble house of Pomys” in the15th Century, the château was probably built on the foundations of the old medieval building.

A busy port in the 15th Century

After their defeat at the Battle of Castillon in 1453 that marked the end of the Hundred Years War, the English continued to trade with Guyenne. They often enjoyed the support of many of the Bordeaux region’s inhabitants, disgruntled at losing their privileges after the French re-conquest. This situation endured for many years and led to the authorities strengthening the estuary’s defences. In 1469, Louis XI banned English navigators from sailing up the Gironde beyond Saint-Estèphe’s port, Notre-Dame-Entre-Deux-Arcs. Due to this fortunate political decision, the port of Saint-Estèphe then enjoyed a period of prosperity, not unlike that of Gallo-Roman times, as for many years Saint-Estèphe thus replaced the port of Bordeaux and could, it seems, accommodate up to 200 boats! The river remained the most popular method of transport, more reliable than “la Levade”, the old Roman road. There were many boatmen and ferrymen willing to proffer their services.

A new landscape to welcome the vine

The marshy island landscape was to change in appearance from the 17th Century with the draining of the marshes by the Dutch at the request of Henry IV and the stabilization of silty ground that would increase the area of dry land. This restructuring saw the disappearance of large bodies of water, to be replaced by esteys, which helped the natural flow of the water. The port of Saint-Estèphe was very busy during this period partly due to the wine trade. Boats could dock easily because of its advantageous location. With its forward position, the port was protected when the estuary was rough. During the same period, the Lords began to clear the forests and heaths and a landscape of vineyards on sunny slopes became more widespread.

After the religious wars, which brought fresh turmoil, the18th Century was a period of respite during which Saint-Estèphe was able to structure its vineyards.

Marc-Antoine Lalanne, the priest who turned Saint-Estèphe into a model parish

At the dawn of the 18th Century Saint-Estèphe emerged from hardship and at last knew prosperity. Obviously the vine was a contributing factor in this newfound affluence. It is known that at this time, the Saint-Estèphe tithe was by far the biggest in all Medoc. This economic growth driven by the wine growing activity brought with it an increase in population. The inhabitants were fortunate to have a strong-minded priest. Marc-Antoine Lalanne started his career as vicar in Saint-Estèphe in 1741. He turned Saint-Estèphe into a model parish. The outside of the church at Saint-Estèphe may be modest, except for the neoclassical-style facade and bell tower built by Duphot in 1855, but the richly decorated interior is one of the most beautiful baroque collections of 18th Century Gironde and reflects this parish’s influence and wealth in the “Age of Enlightenment”.

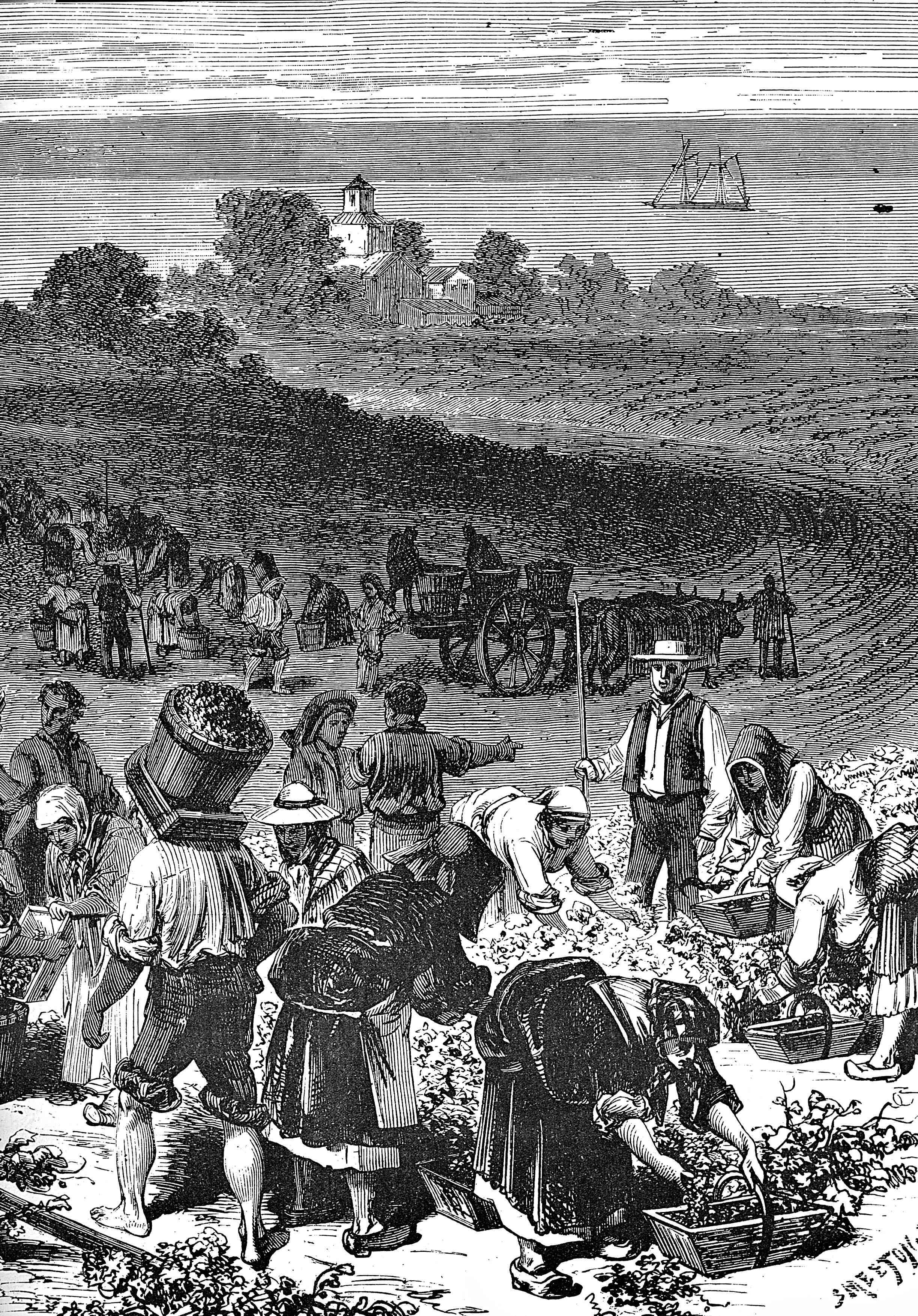

The creation of the vineyards or “planting fever”

An important change was to take place in the 18th Century. Until then polyculture had been the norm and a light wine, called ‘claret’ by the English, was being produced. This completely unprepossessing wine was to give way to a red wine, which from that time on would enjoy international fame and would be the making of the appellation’s reputation. The reparcelling of the land that began in more recent times would enable the creation of wine estates. In the same period, the quality reputation of the terroirs and the wines produced from them was growing. Strong interest in wine growing led to new land being sought for cultivation. In 1790 Father Lalanne could count a total of 200 vineyard owners in his parish.

It was already recognized that a well-managed vine was more profitable than cereal. Vines had been grown on the land around Bordeaux known as “las Gravas de Bordeaus” for a long time. Within the Medoc, Saint-Estèphe in particular had already started converting to wine growing from the 13th Century but was still under-exploited. Wealthy Bordeaux members of parliament became interested in this region north of Bordeaux and set about an out-and-out colonisation. This interest was heightened by the concept of “Cru” that had been growing in importance since the early 18th Century due to the ingenuity of the Pontacs, owners of Haut-Brion and the Seigneury of Pez in Saint-Estèphe. The wine, which was at that time referred to as the “New French Claret”, had improved considerably and was very popular with an international clientele. Similarly, the concept of vintage seems to have appeared from 1708. Saint-Estèphe therefore saw new investors buying up and reparcelling land to plant more numerous and more extensive “plantiers” (large vineyards). In Saint-Estèphe the vine became almost the only crop. Its omnipresence was such that Boucher, the Intendant, and his successor, Tourny, became concerned that poverty in some parts of the population and the lack of cereal production would lead to a famine like the one of 1758.

Powerful property owners

In the 18th Century some powerful noblemen, heirs of a feudal structure, could be found in Saint-Estèphe. There were direct seigneuries such as those of Lesparre, the noble houses of Calon, Pez, and Pomys. There were also the fiefdoms of Bardis, Vallée Roussillon and Breuil. The Saint-André de Bordeaux chapter held the Courts of Saint-Corbian, while Blanquet and Leyssac answered to the Lord of Breuil. New property owners, who were Nobles of the Robe, (mainly Bordeaux members of parliament), and foreign merchants also invested in Saint-Estèphe vineyards. Aristocrats and bourgeoisie alike succumbed to “planting fever”.

In the mid 18th Century, Calon belonged to the son of Alexandre de Ségur nicknamed ‘the prince of the vines’ as he had bought Mouton in 1718 after inheriting Lafite and Latour in 1716. To him we owe the declaration, «I already make wine at Latour and Lafite, but my heart is at Calon”.

Rochette, at the site of the present day Château Lafon-Rochet, already consisted of a large vineyard whose origins date back to the 16th Century and belonged to the Lafons, counsels at parliament. The noble house of Pez belonged to the Count de Fumel, parliamentary counsel.

Guy Lacoste de Maniban, Lord Knight of Estournel, president of the Court of Aids, owner of the noble house of Pomys, bought the vineyards on the Caux hill in 1758. His son Louis Gaspard d’Estournel throughout his life continued the re-parcelling started by his father and, between 1790 and 1853, exchanged and bought around a hundred plots from small tenants or lords to create his estate on the hill of Cos, part of which was already occupied in the 18th Century by the Cos Gaston property that was to become Château Cos Labory.

Théodore Desmoulins inherited some vine plots in Fontpetite in the late 18th Century, and decided to clear the neighbouring woodland known as the “Lande de l’Escargeon” (Escargeon’s heath) covered in pink heather. As a result, he revealed the prestigious terroir of the future Château Montrose. In the 18th Century, another old Saint-Estèphe vineyard, Château La Haye, belonged to the Arbouet de Bernède, a family of merchants who had made its fortune in the island colonies. According to legend, the château (part of which dates from the16th Century) was the place where King Henry II and Diane de Poitiers used to come to hunt. The interwoven letters H and D can be seen carved in the stone above the doors.

The success of the wines also attracted foreign merchants who came to Bordeaux to set up wine merchant companies. These merchants of English or Irish origin bought properties and played their part in the development of the vineyards. This was the case of the Basterots, Ségurs or Phélans, whose names have become attached to the Phélan-Ségur and Ségur de Cabanac estates.

The MacCarthys (the name survives today as the second wine of Château Haut-Marbuzet) were very much part of society as a member of this family was president of the Bordeaux Chamber of Commerce in 1767. The famous Bordeaux merchant, Thomas Barton, of Irish origin, farmed a large estate in Saint-Corbian (the Boscq estate). His grandson later set up in Saint-Julien.

The greatest vineyards may have belonged to the Nobles of the Robe, to the upper middle classes or rich merchants, but Saint-Estèphe has always had a large number of owners native to the appellation and possessing properties no larger than 5 hectares. These bourgeois vineyards have left a strong mark on the village and have given the future appellation an identity that is “peasant” in the original, noblest sense of the word.

After the golden age of the 18th Century, there was a succession of crises that led to the châteaux changing hands. The French Revolution did not spare Saint-Estèphe, some owners went to the guillotine and their properties were confiscated and sold as national property. This is what happened to Meyney that had belonged to the Feuillants since 1622. Other owners, such as the Marquis de Ségur, chose to emigrate.

From 1825, which was a great vintage, business picked up again for quite some time. The medieval priory-barns, the bourdieux, (Bourgeois country properties), the first buildings, had long since disappeared to be replaced by châteaux of varying architecture. Superimposing the term “château” over that of “cru” without doubt played some part in the frenzied construction of large number of chateaux in the 19th Century. Not all ”Cru” land contained seigniorial buildings, most of the new estates came from parcels of feudal seigneuries. The new purchasers therefore believed it important to construct or reconstruct a château worthy of the name on the site of an old building. In the latter part of the 19th Century, new purchasers, wealthy businessmen, industrialists, French and foreign bankers bought the crus and developed them. At Montrose the visionary entrepreneur Dolfus turned the cru into a model estate by creating a village with streets and small squares. London banker, Martyns, bought Cos d’Estournel, Cos Labory and Pomys.

If the 1855 classification only includes 5 crus classés in Saint-Estèphe, this is probably linked to the fact that many estates lacked structure at the time, and to the area’s distance from Bordeaux. As Saint-Estèphe is the most northern of the prestigious appellations, it of course took longer for the Bordeaux brokers to reach and they therefore went there less often than they did the other appellations. But Saint-Estèphe can hold its head high alongside its neighbours regardless; its early history, the great diversity of its terroirs, the unquestionable prestige of its Crus Classés, the strength of its many crus bourgeois mainly from the most “noble” terroirs, are the pride of the appellation.

Saint-Estèphe is a wine-producing village that has kept its vine-grower’s soul, close to the vine that is rooted so deeply in its history. Nonetheless, this does not prevent it from being at the forefront of progress thanks to new buyers willing to invest in turning their cru into a model of modern wine making, with innovative cellars that are amongst the finest in the world. But this is not really surprising because, looking back, we can see that there have always been forward-thinking men, who have gone “all out” to produce excellent wines. In so doing, they have contributed to quality improvements within the vineyards and to the reputation of the appellation’s wines. But what is new is that this determination has been passed on to the more modest wine growers who are now bringing out the very best of their production. The image of Saint-Estèphe is one of tradition and modernity in perfect accord. An extract from the 1806 testament of the owner of Tronquoy Lalande, François Tronquoy Lalande, to his son reminds us of the good sense of the Saint-Estèphe wine grower: “ …So you find yourself with a fine fortune gained through my efforts and hardships; but beware, you might lose it. It could turn to nothing and expenses ruin you, if you do not cultivate it with great care, with pleasure even. So, if you are proud to call yourself a farmer and truly love agriculture, you will realize that real wealth, the greatest wealth, comes from country property, above all from that which will be yours; that to tend to it is an occupation which is the most noble, most satisfying, most useful and most worthy of an honest man... ”

Book produced for the Syndicat Viticole de Saint-Estèphe, Design and writing: Catherine di Costanzo

Graphic design: Virginie Obrensstein

Pictures: Christian Braud and Claire Guira

Illustrations: Vincent Duval

Photographs: municipal archives of Bordeaux, photos Bernard Rakotomanga

Map: "lithology Pierre Becheler", geographer: Jean-François Dutilb

English translation: Carine Bijon

Comments