When coming up from the south, leaving behind the commune of Pauillac, visitors can take one of two routes to Saint-Estèphe: the inland road known as the “route des châteaux” (the châteaux road) and the estuary route, commonly known as the “route du fleuve” (the river road). Both are voyages of discovery. The “river road” is the only road in the Medoc that runs alongside the estuary for over 8kms. Here the river imparts such serenity that it seems to have transmitted it to the vines that contemplate it. Only the river’s slow respiration over the marshes shows that it is living and it is difficult to imagine that once, thousands of years ago, it was a wild river, carrying along with brute force stones and pebbles from the distant Pyrenees and Massif Central mountains. The Saint-Estèphe vineyards were born of the river and this is how we understand the Medoc’s history when we travel along the “river road”.

By the river road

The atmosphere of the estuary banks is unique and deeply marks the area. In the morning the river is shrouded in a light mist that slowly evaporates. Its waters reflect the changing and mixed hues of the sky, sometimes blue, sometimes grey with glints of gold. Its untamed shores are home to wooden shrimp fishing huts. The fishing from these huts, perched on their long acacia posts and sporting graceful fishing nets, leaves much to chance and is regulated only by the tides. Nature lovers enjoy getting together here.

When taking this estuary road, the walker discovers the secrets of the Saint-Estèphe vineyard landscape. From the banks his gaze spans the marshland and, rising in the background, he spies the beginnings of the gravelly slopes on which the châteaux stand.

The river reminds us that the Saint-Estèphe vineyards were born from the river, its resources, its influence on the climate and the part it plays in the transport and trading of wine. Nowhere but on the banks of the estuary is there so much interdependence between man and his land.

By the road of the castle

Still heading up from the south but taking the other, inland road, we come into Saint-Estèphe via a depression, the ‘Jalle du Breuil’ (Breuil Brook), where there is an estey, a kind of small stream that serves as a natural boundary between Pauillac and Saint-Estèphe. This road that runs through the appellation’s hamlets crosses a graceful vineyard landscape. Here we come across châteaux of various styles, pale stones, railings and immaculately straight rows of vines.

Visit the village through its hamlets, their names steeped in history.

Saint-Estèphe contains around twenty hamlets or villages. To obtain a complete picture of the commune, start from the river road that here serves as the base of a semi circle whose centre is at Meyney and travel up inland from south to north, in a clockwise direction.

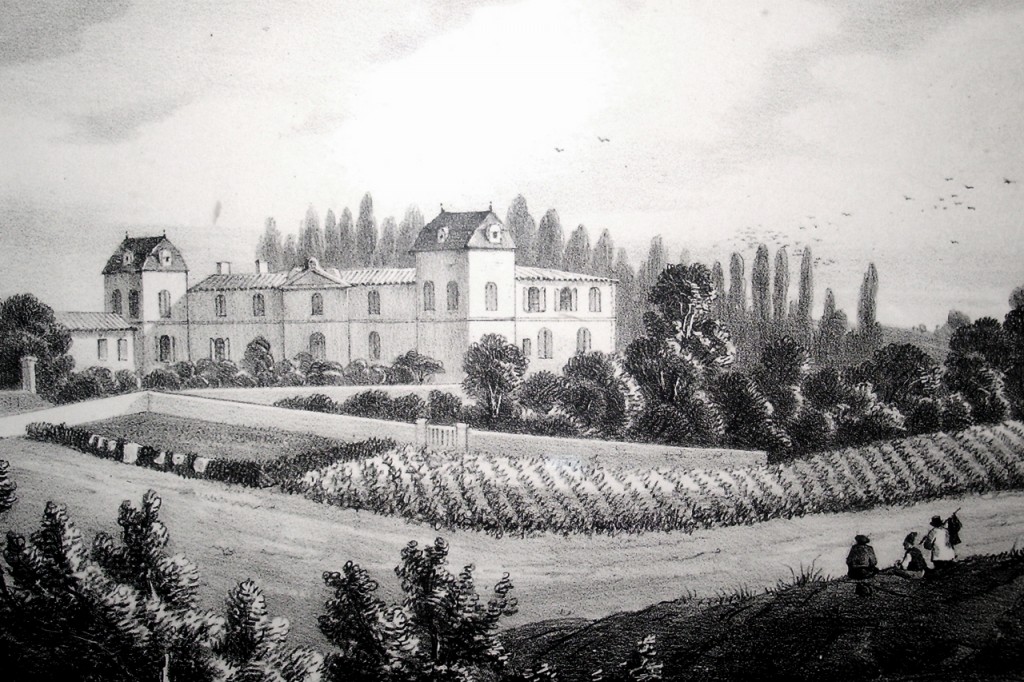

Meyney, located on the estuary bank at the site of the present day château of the same name, is undoubtedly the birthplace of the Saint-Estèphe vineyards. Vine growing here probably dates back to Gallo-Roman times. It is known that, in the 13th Century, there was already a self-sufficient priory growing cereals and vines. At the time, the “Maison de Coley” (House of Coley) belonged to the Calon seigneury (landed estate), one of the largest and oldest in the Medoc. Then, in the 17th Century, the monks of the Feuillants religious order developed the lands and created the vineyard that became one of the pioneers of modern viticulture.

The hamlet known as Montrose is wholly represented by one of the jewels of the appellation, Château Montrose, grand cru classé. The present day vineyard was originally heath land covered in pink heather known as “la Lande de l’Escargeon” (Escargeon’s heath). The term “Mont” relates to the gravelly hillock morphology. Montrose’s soils have shown themselves to be excellent for vine growing. The complex terroir is made up of sand and clay subsoil, topped by coarse graves.

Still in a clockwise direction and slightly further

south, the hamlets of Marbuzet and German

together create a large village that includes an upper

part, “Marbuzet”, and a lower part “German”.

The name Marbuzet appears to be of Latin origin, “marga” signifying marl and “buxea” meaning

surrounded by woods. The soils are gravelly and

clayey-limestone. The hamlet’s châteaux are

Marbuzet, La Croix de Marbuzet, Haut-Marbuzet

and Le Crock. In the village, the “chemin de la

fontaine” leads to one of the prettiest fountains in

the region.

A little further south, along the D2 known as the “Route des Châteaux”, the village of Cos marks the beginning of the Saint-Estèphe appellation. Cos was written “Caux” until the 19th Century, meaning “the hill of pebbles” in old Gascon language and reflects the morphology and composition of this exceptional terroir. A very marked depression, known as “la Jalle du Breui” (Breuil Brook) separates Château Lafite-Rothschild’s vineyards from those of Cos d’Estournel and provides excellent drainage with natural water outflow. The village of Cos boasts two grands crus classés: Château Cos d’Estournel, whose exotic architectural style - a kind of Indian temple dedicated to wine – surprises and delights the visitor, and Château Cos Labory, with its opulent, bourgeois facade, which has belonged to the Audoys, a Saint-Estèphe family, for several generations.

Continuing along the D2, we can admire the great gravelly plateau of Cos extending as far as Rochet, whose meaning refers to the ‘roches’ (rocks), i.e. the graves, which cover its soil. Here the beautiful yellow ochre colour covering the walls of the building and cellars of Château Lafon-Rochet, grand cru classé, draws the visitor’s eye.

Facing Rochet is the village of Blanquet, whose terroir, as its name suggests, is distinguished by patches of white that come from the limestone and alluvial gravel in its composition. Blanquet was home to the old, now disused, Saint-Estèphe station. We pass Château Andron-Blanquet in this village.

Continuing our circle, but further west, we come to a local spot known as Ladouys where Château Lilian Ladouys stands. “La doys” can be traced back to the 16th Century. The soil in this part of the appellation is made up of sandy-gravelly alluvia mixed in the depths with marl and clayey limestone.

Still to the west but travelling up, lies the hamlet of l’Hôpital de Mignot, located on the borders of the Cissac commune. The origin of its name dates back to the hospitaliers (monks) of Saint John of Jerusalem who built a chapel there to receive pilgrims and travellers. This hamlet has the distinction of rising to 30 metres’ altitude. From a lithological point of view, it stands at the junction of different terroirs, there is a sandy-clay formation as well as marl and clay from the Oligocene epoch, massive banks of limestone, marl and lacustrine limestone, clayey limestone and valley bottom sands. The châteaux of Martin, Haut-Laborde and Coutelin-Merville are located here. Further on there is the hamlet known as Coutelin with Château Haut de Coutelin.

Leyssac is the second most important village in the commune. There was even a time when it rivalled the village of Saint-Estèphe with its own schools, shops, chapel and village festival. Groundwater flows from the Leyssac water table to Saint-Estèphe along the slope of the rocky substrate. The village is situated on gravelly and clayey limestone soil. The châteaux of this large village are La Peyre, La Rose Brana, La Commanderie, La Haye, Saint-Estèphe, Pomys, Clauzet, Plantier Rose, and L’Argilus du Roi, and there is also a cooperative winery.

A little further west we come to Brame-Hame, a gascon name that means “weep-for-hunger” and recalls a time long ago when starvation and famine blighted the village. The château of the same name can be found in the hamlet. The soil is made up of clayey and marly limestone.

Continuing west, the hamlets of Pradines, Troupian and Lavillotte sit on limestone, sandy and sandy-clay terrains. Here we pass Châteaux Rémandine, Lavillotte, and De Côme. The Vertheuil road links these hamlets to Laujac, home to Chateau Tour Saint-Fort. In this locality and the area further north, the Saint-Estèphe limestone dates from the Eocene Epoch. It is not uncommon to find superb sea fossils when walking through the vineyards.

Further north we come to the hamlet of Aillan where Château Sérilhan is situated. Of the commune’s four fountains, the one in Aillan was built to serve as a lavoir (wash house) and still has a running spring feeding it.

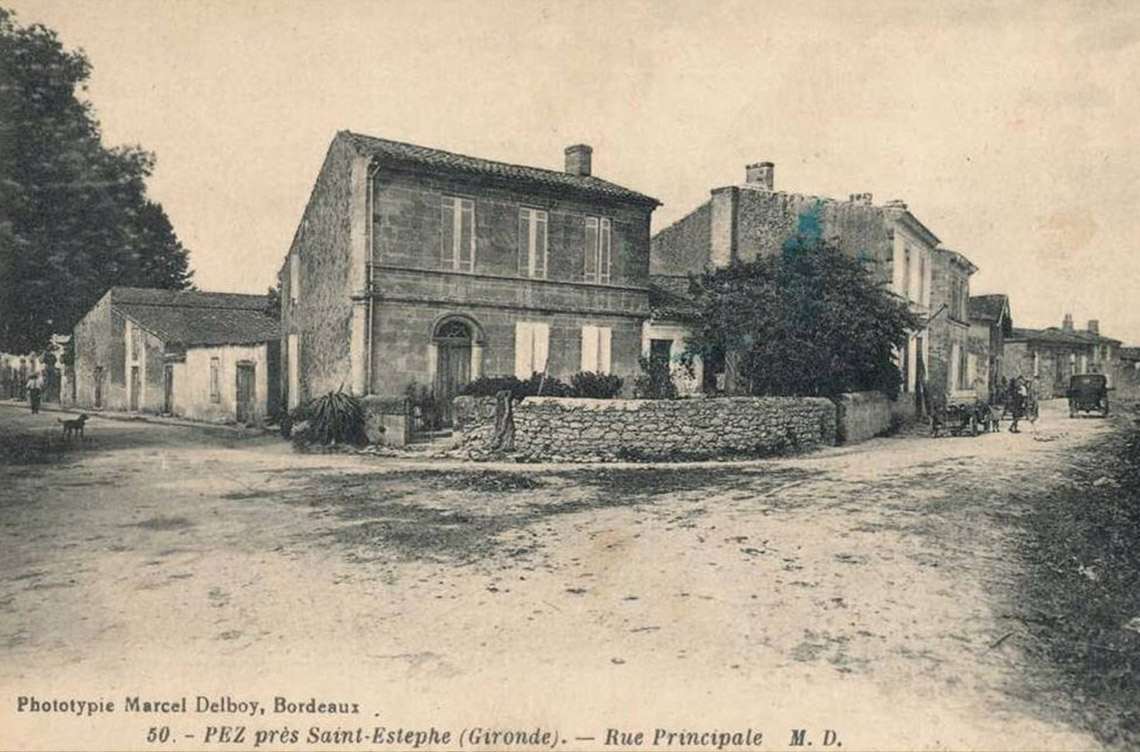

Then, l’Hereteyre, which means “land of iron” in old gascon language, joins up with the hamlet of Pez that boasts several châteaux including Petit-Bocq, de Pez, Ormes de Pez, and Tour de Pez. The word “Pez” comes from “pès” meaning Roman foot. These hamlets are situated on gravelly and clayey limestone soils.

The most northerly village in the Saint-Estèphe commune, through which the D2 runs, is Saint-Corbian. Here we can admire an old dovecote and a fountain. Situated on gravelly soils, then sandy-gravelly and clayey limestone soils, Saint-Corbian is separated from its neighbouring commune, Saint-Seurin de Cadourne, by the chenal de Calupeyre (Calupeyre channel), which extends as far as Saint-Germain d’Esteuil and by which we can access the Brion Gallo-Roman site, which may perhaps be the famous lost Roman city of Noviamagus. Saint-Corbian was once an island surrounded by the waters of the vast Reysson marsh. Its name is said to have come from “courbian”, which means “end of the marshes”. In this village, we find châteaux Tour des Termes, Beau-Site Haut-Vignoble, Haut-Coteau, Beau-Site and further north, Le Boscq.

Coming back down towards Saint-Estèphe village we come to Calon, an old site that is home to the appelllation’s grand cru classé, Château Calon-Ségur. “Calon” is said to come from Calonès that may mean “small wood carrying vessels or longboats”. It is very likely that this meaning refers to the time when the channel, which used to cross the great Saint-Corbian marsh and border the parish, was navigated. The noble house of Calon was an important fiefdom in the Middle Ages. In the 17th Century the rich Ségur family stamped its name on the history of this wine, particularly Alexandre de Ségur, nicknamed “the prince of the vines”, who presided over Lafite and Latour, amongst others. The old building with its gravelly, undulating vineyards, protected by long stone walls, is an exceptional site close to the village.

The village itself consists mainly of stone houses. In the square we find a magnificent baroque church rebuilt in the 18th

Century. The main part of the village contains about fifty houses, mostly in 19th Century style, and a parish church with a small closed square. Around this church lie five distinct districts: Garamey, Lacroix, Picard, Canteloup and Fontaugé. Châteaux Valrose, Domeyne, Haut-Beauséjour, Picard, Bel-Air, Capbern Gasqueton can be found here and, slightly further east, Château Phélan-Ségur in a little hamlet known as Garamey.

Further inland, the place known as Lalande lies on gravelly soils and is home to Château Tronquoy-Lalande. Here we notice the orangey colour of the earth that comes from the composition of its gravelly soil.

A little further west, Carcasset, where we pass Château Laffitte-Carcasset, sits in the centre of Saint-Estèphe’s gravelly plateau.

We complete our semi circle in the district of the Port, which is no longer in use. Château Ségur de Cabanac and its graves vineyards face the estuary along with a few other buildings. Here there is a restaurant-bar, and a picnic area where in fine weather you can enjoy a drink or lunch while watching the boats sail past.

In earlier times this spot was called la Chapelle (the chapel), but is today renamed les “allées marines” (the marine lanes). The boats and the fishermen came in to attend mass here. It is a peaceful area. Once a year, the traditional “foire à la chapelle”, which has medieval origins, takes place. Here we can find anything and everything, from work overalls, carousel rides and bags of sweets, to cars and tractors or wine to sample. Traditionally it is called “the garlic and onion fair ” and takes place around the Sunday of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin in early September. At the port of la Chapelle, we finish behind the hamlet, by the old mill, a reminder of the importance of this region’s activity before the rise of the wine-growing business.

Book produced for the Syndicat Viticole de Saint-Estèphe, Design and writing : Catherine di Costanzo

Graphic design: Virginie Obrensstein

Pictures: Christian Braud and Claire Guira

Illustrations: Vincent Duval

Photographs: municipal archives of Bordeaux, photos Bernard Rakotomanga

Map: "lithology Pierre Becheler", geographer: Jean-François Dutilb

English translation: Carine Bijon

What was the harvest like at the beginning of the 20th century? The harvest is done in common and is an occasion of sociability, neighbors and entire families, everyone, from grandparents to children participate. It was an important event in rural life and was accompanied by numerous celebrations. At this time, the harvesting of the grapes is done mainly by women assisted by their children, while the transport is the exclusive business of men who then carry out the entire process of wine making !

(c) Région Nouvelle-Aquitaine, Inventaire général du patrimoine culturel. Château Laffitte Carcasset - Carte postale, début 20e siècle (collection particulière)

Comments